The opening statement on Hiroshima’s Peace Memorial Park’s (平和記念公園, Heiwa Kinen Kōen) website:

A single atomic bomb indiscriminately killed tens of thousands of people, profoundly altering and disrupting the lives of the survivors. Through belongings left by the victims, A-bomb artifacts, testimonies of A-bomb survivors, and related materials, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum conveys to the world the horrors and the inhumane nature of nuclear weapons and spreads the message of “No more Hiroshimas.”

Before the bomb, the area of what is now the Peace Park was the political and commercial heart of the city. For this reason, it was chosen as the pilot’s target. Four years to the day after the bomb was dropped, it was decided that the area would not be redeveloped but instead devoted to peace memorial facilities.

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial (Genbaku Dome) was the only structure left standing in the area where the first atomic bomb exploded on 6 August 1945. It has been preserved in the same state as immediately after the bombing. Not only is it a stark and powerful symbol of the most destructive force ever created by humankind; it also expresses the hope for world peace and the ultimate elimination of all nuclear weapons.

The whole of the park is beautifully landscaped. We came across this wonderful rose garden. Imagine the sight and aroma in springtime.

The Flame of Peace marks the centre of the park. Designed by Kenzo Tange, then professor at the University of Tokyo, the base of the sculpture represents two wrists joined together, and the two wings on either side represent two palms facing upwards to the sky. It was designed both to console the souls of the thousands who died begging for water and to express the hopes for the abolition of nuclear weapons and the realization of lasting world peace. The flame at the top was lit on August 1, 1964, and has been burning ever since in protest of nuclear weapons, and will continue to burn until there are no nuclear weapons left on earth.

The importance of children permeates the message of the Peace Park: the many that suffered instantly on 6 August 1945; those who survived and suffered thereafter; and children as torch bearers for the hope of a peaceful future.

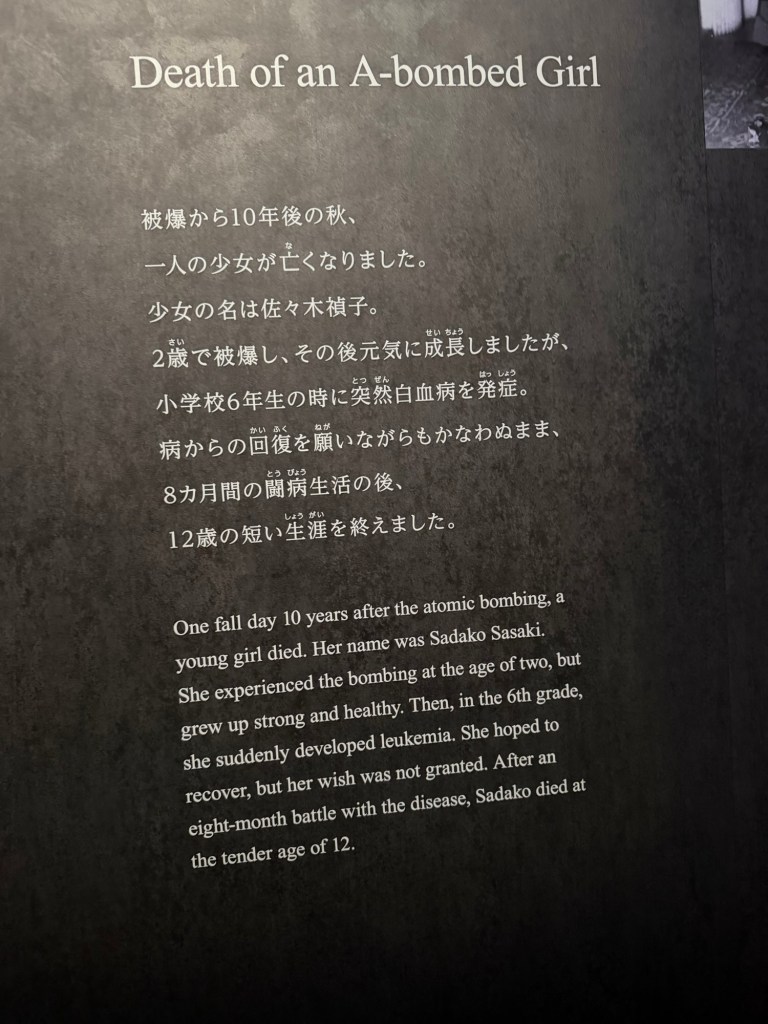

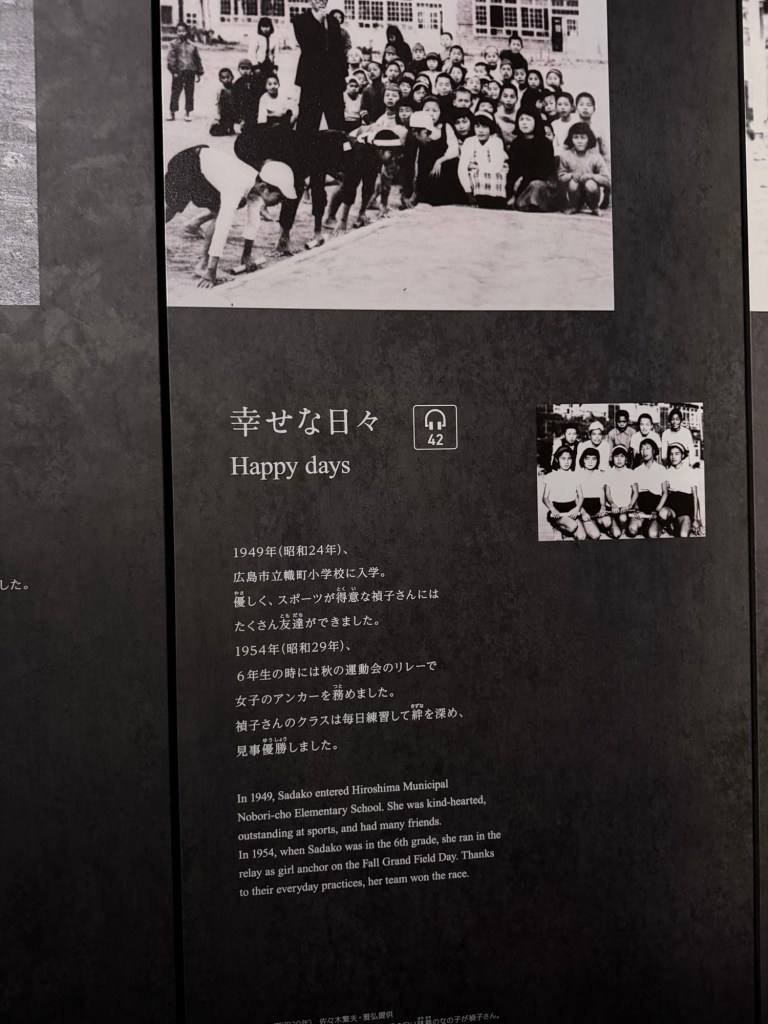

Around the park and the city one will see brightly colored paper cranes everywhere. These paper cranes come originally from the ancient Japanese tradition of origami or paper folding, but today they are known as a symbol of peace. They are folded as a wish for peace in many countries around the world. This connection between paper cranes and peace can be traced back to a young girl named Sadako Sasaki, who died of leukemia ten years after the atomic bombing.

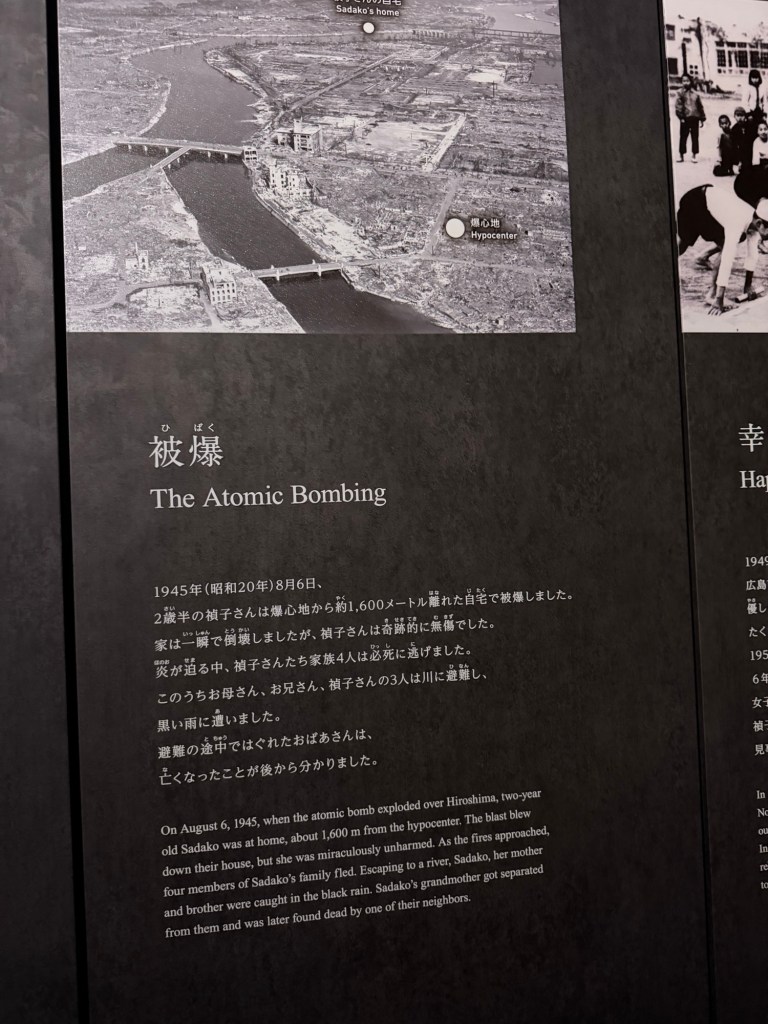

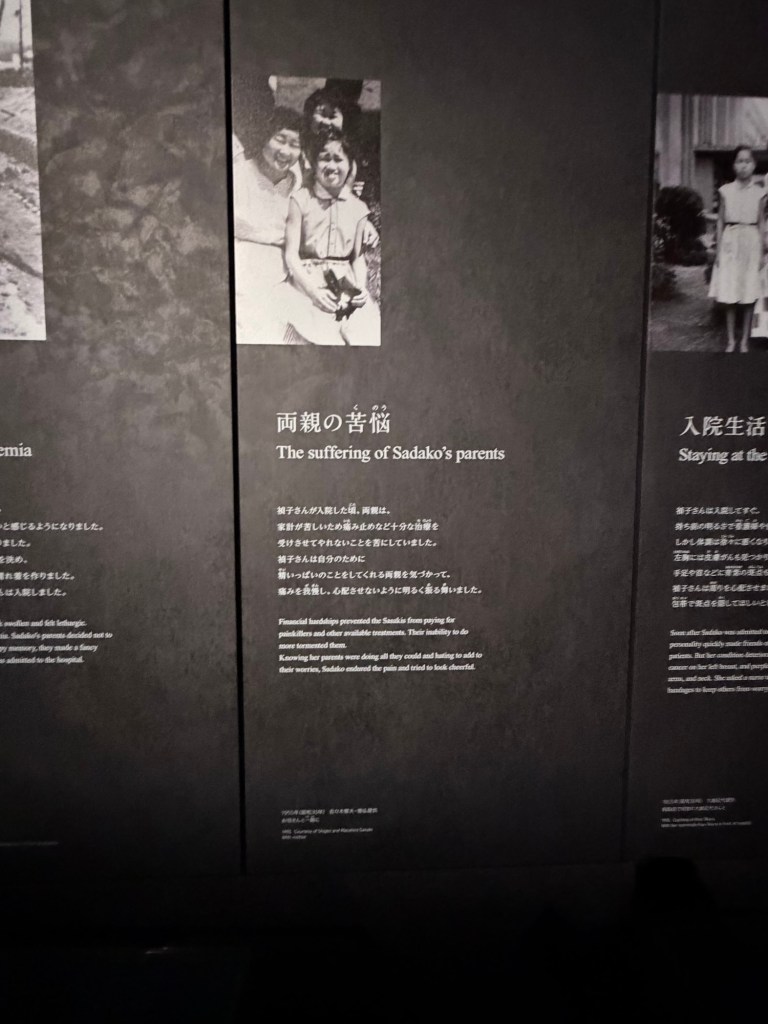

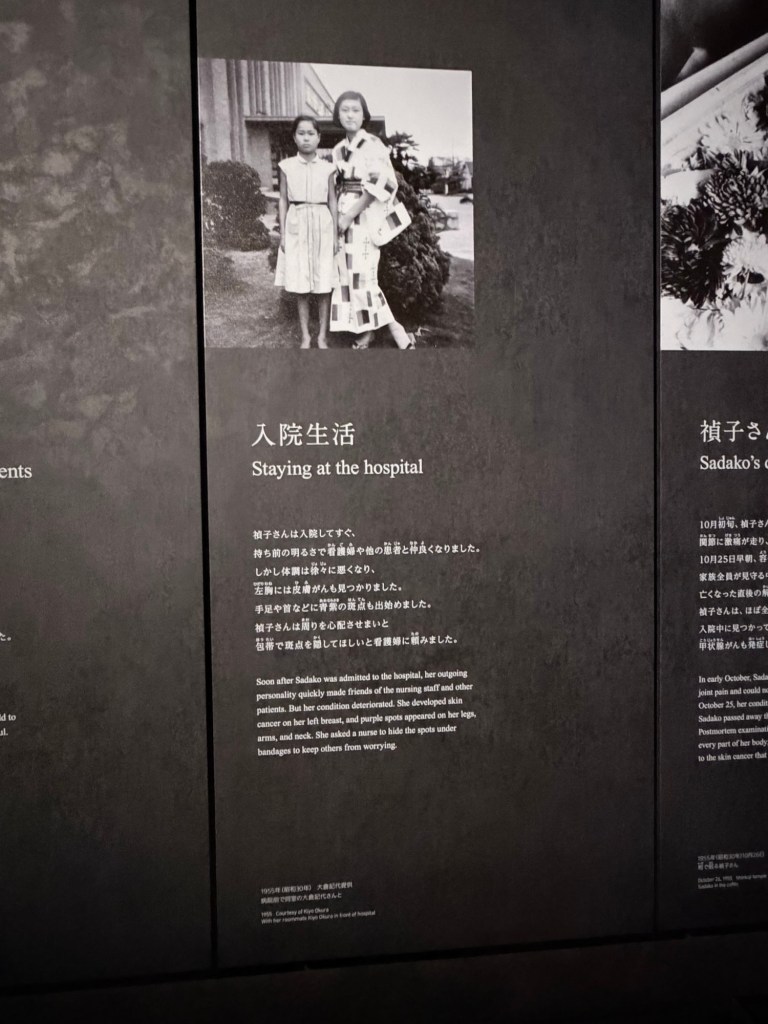

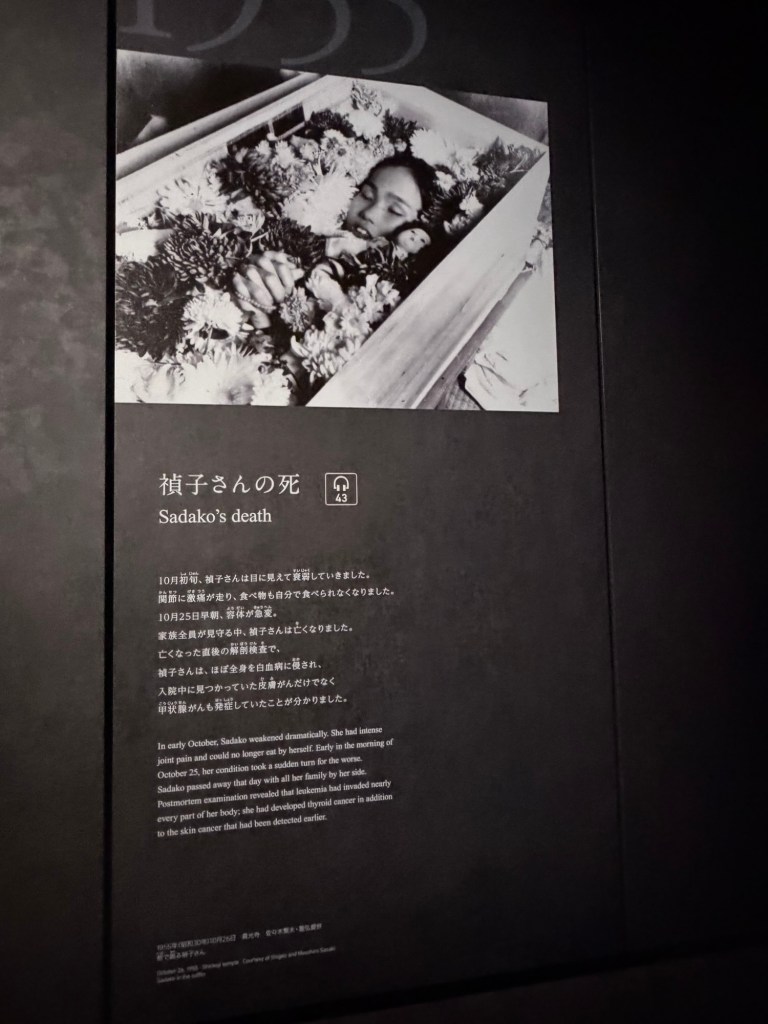

Sadako was two years old when she was exposed to the atomic bomb. She had no apparent injuries and grew into a strong and healthy girl. However, nine years later, she suddenly developed signs of an illness. In February the following year she was diagnosed with leukemia and was admitted to the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital. Believing that folding paper cranes would help her recover, she kept folding them to the end, but on October 25, 1955, after an eight-month struggle with the disease, she passed away.

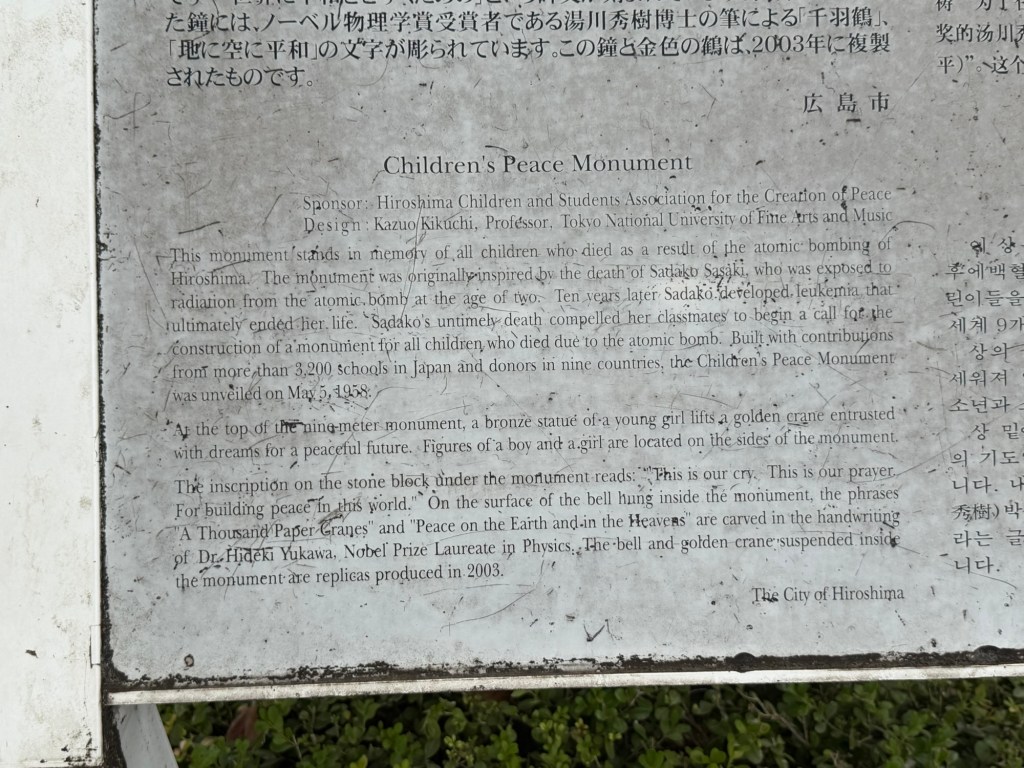

Sadako’s death triggered a campaign to build a monument to pray for world peace and the peaceful repose of the many children killed by the atomic bomb. The Children’s Peace Monument is the result, built with funds donated from all over Japan. Later, this story spread to the world, and now, approximately 10 million cranes are offered each year before the Children’s Peace Monument.

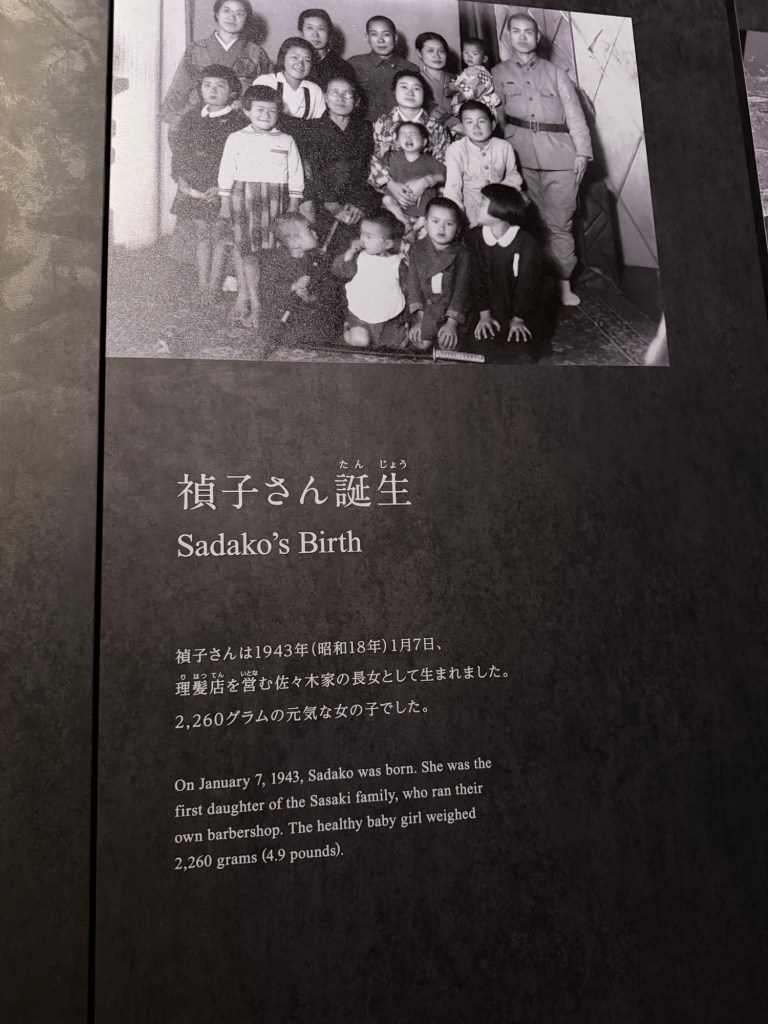

An exhibit in the museum honours Sadako. This series of images attempts to replicate the exhibit.

Sadako was, of course, one of many children who suffered.

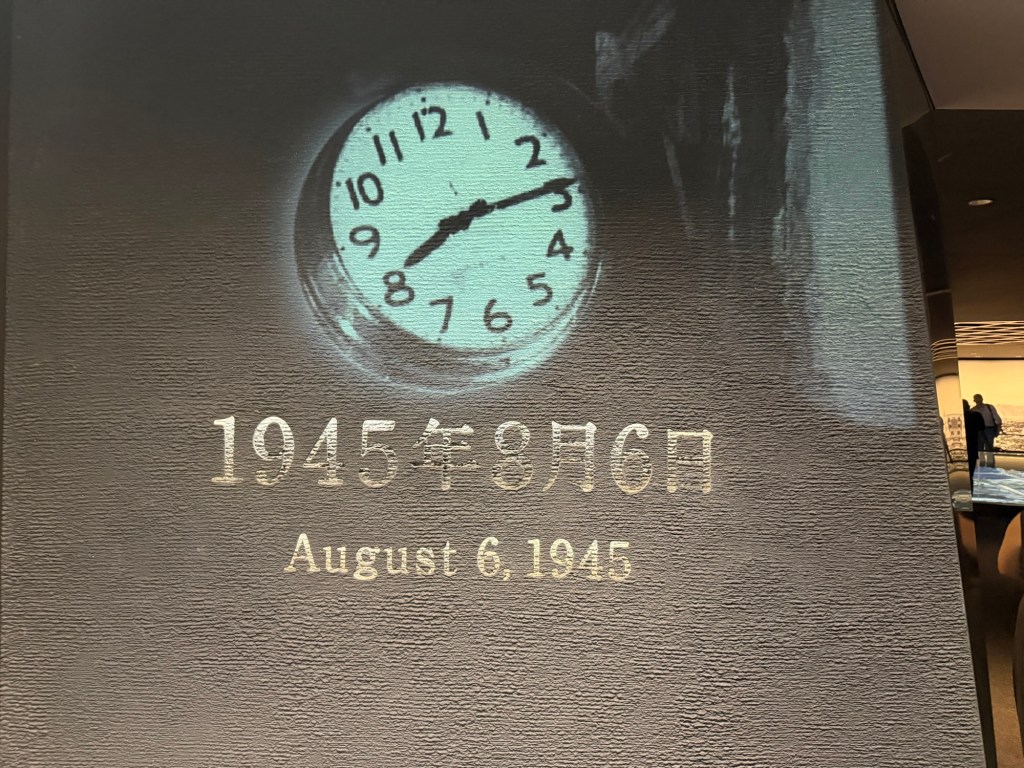

The harsh reality of this cataclysmic event is starkly laid out within the museum itself.

Shinichi Tetsutani (1 year, 3 months) was riding this tricycle when the A-bomb dropped. Suffering serious injuries and severe burns all over his body, he died that night. His father, Nobuo, buried Shinichi’s body in the backyard, along with his tricycle, so that he could ride it even after his death. The family lived 1500m from the hypocentre.

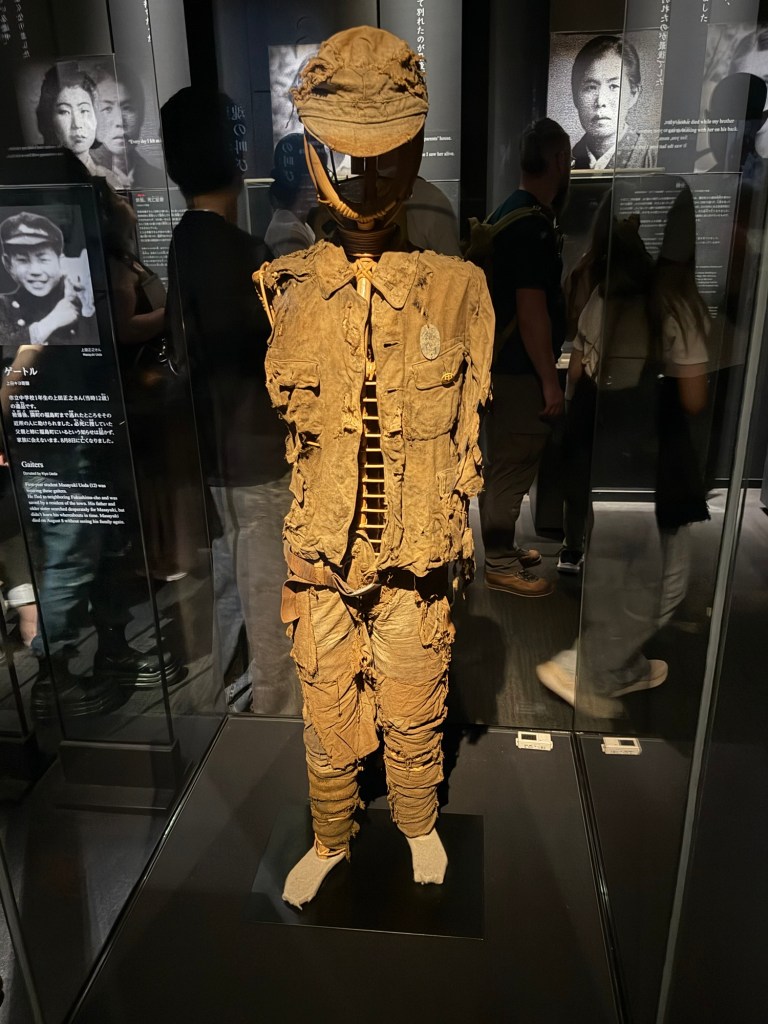

900 metres from the hypocentre, a group of first- and second-year students from Hiroshima Junior High School were hit by the blast. Most of them died. This exhibit displays the clothes worn by three of them killed in the blast. Each article conveys the deep sorrow felt by the parents on the loss of their sons.

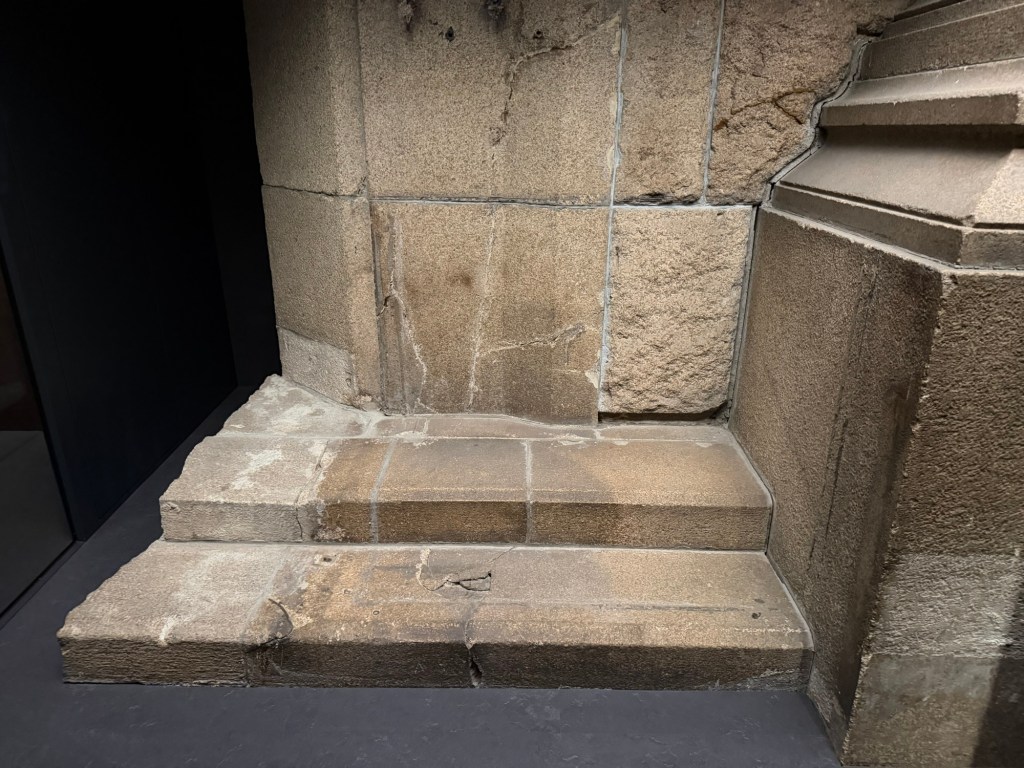

One thing stood out as a marker of what made this event horrifically unique. Black shadows of humans and objects, like bicycles, were found scattered across the walkways and buildings of Hiroshima in the wake of the atomic blast. If difficult hard to fathom, these shadows likely encapsulated each person’s last moments, similar to the ashen casts of ancient volcano victims preserved at Pompeii. When the bomb exploded, the intense light and heat spread out from the point of implosion. Objects and people in its path shielded objects behind them by absorbing the light and energy. The surrounding light bleached the concrete or stone around the “shadow.”

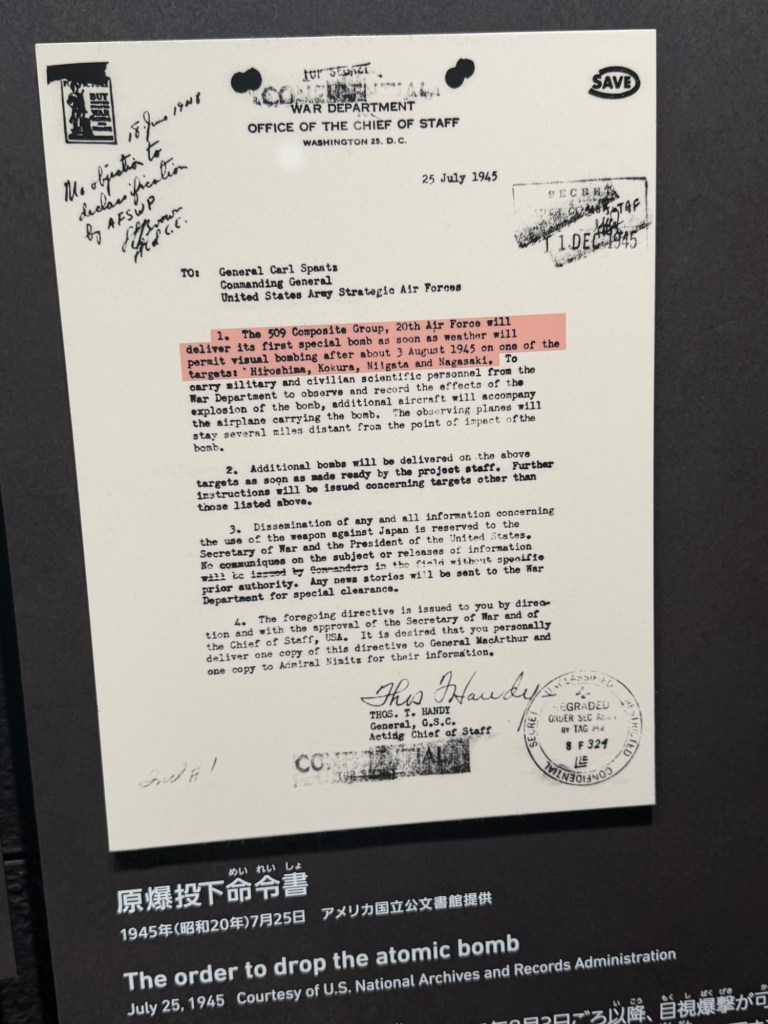

And here it is, the order that changed the world forever.

I am dividing today’s blog into two sections, A and B. It would be insensitive not to do so.

A final thought:

Leave a comment